Naming the Dead

Robin Reineke, The Colibrí Center for Human Rights

Estela had been living in the US for several years. She had immigrated so that she could get a reliable job and support her son who stayed behind with his grandparents in Mexico. After awhile, she couldn’t bear it anymore—she returned to Mexico to retrieve her boy. She hired a coyote to guide them over the border into Arizona with a group. A couple of days into the journey, she became delirious from the heat. Her son kicked and struggled against the people who pulled him away from his mother when they left her body behind in the desert. He was five years old. He told me that he put his jacket over her before they left her behind.

Estela is now one of over 1,500 missing people last seen crossing the border into Arizona. I can visualize her white tennis shoes and her blue shirt. Her gold earrings and her black glasses. Her smile. These images are always in my mind when unidentified skeletal remains for women in their late 20s and early 30s are found. They are found too often.

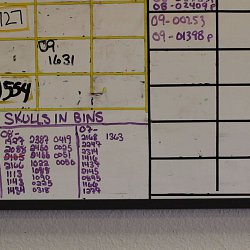

Thousands of Mexican and Central American migrants have died along the US-Mexico border over the last decade, and many of them still lie unidentified, in unmarked graves. This human rights crisis is growing increasingly dire. An average of 170 bodies are found each year in Arizona, a number that has not decreased in over a decade despite a decrease in overall migration from Mexico. Meanwhile, the deaths are increasing in the border counties of southern Texas, with one small county recovering 129 bodies in the year 2012. The bodies are being buried, cremated, even scattered at sea without names. Meanwhile, thousands of families like Estela’s are actively and painfully searching for the missing.

The desert has always been a dangerous place, but the border hasn’t been. It became so only recently, after international trade agreements and US border enforcement policies eliminated the safe paths into the country from the south. Now, the service entrance for thousands of people is through the desert. They are dying on their way to work.

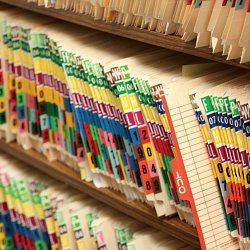

And the staggering loss of life on the border is only part of the tragedy. There is no organized mechanism to identify the dead. Perpetually on the wrong side of the wall, the families are not assisted consistently in their search for missing loved ones. Thousands of bodies are being found on US soil, while thousands of families search from abroad or from within the shadows in the US. I have spoken with relatives of the missing who have listed 20 or more different organizations they have contacted in their search. Each time they are going over the painful details of what happened and the intimate characteristics of the person they love and miss. Each time they are re-living the agonizing uncertainty and holding their breath as they wait for answers. They usually never get any.

But families like Estela’s will tell you, “we are always already thinking about her anyway.” Their lives are on hold. The experience of having a missing person in the family is so deeply destructive; it’s like the entire family goes missing. Daily life becomes fraught with guilt and fear—what if she is out there somewhere in the desert, lost, suffering? Estela’s sister told me, “The only time I feel alive is when I am looking for her.” It is difficult to eat, difficult to sleep. In dreams, the missing visit, asking for help, begging for water or food. The daughter of one missing woman attempted suicide the year after her mother disappeared in the desert. Others have died from health complications that arose from the stress of the disappearance.

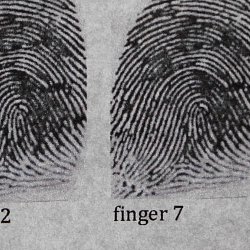

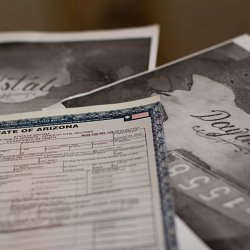

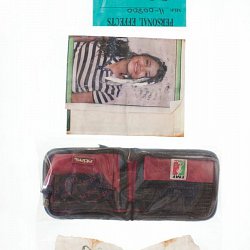

Meanwhile, those examining the dead, like Dr. Anderson in the film, see the same case nearly every day—a young man in the prime of life, dead from exposure, usually already unrecognizable due to the same heat that killed him. Unless he is carrying an identification card, and sometimes even then, the process of finding the family who is searching for him can take years. More than 800 dead in Pima County, Arizona are still waiting to be returned to their families. There is no centralized system—no complete database, no comprehensive DNA program, no single entity tasked with repatriating the dead. The work is diced up between various federal and local jurisdictions that don’t consistently share information. A family who reports a person missing to Webb County, Texas, could wait for years because the body was found in Brooks County, only two counties away. They could wait for years even if they reported to the right county, because their loved one could have been found as a weathered skeleton, unidentifiable without a massive DNA matching system.

There are two hopeful efforts to assist the families of the missing and repatriate the dead. The Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team’s Border Project and the Colibrí Center for Human Rights’ Missing Migrant Project are both working to assist the families in their search, regardless of nationality or citizenship status. Both projects are working closely with governmental and non-governmental players to identify the dead. And both struggle to do the work because of the borders and boundaries that have been constructed in the minds of those in positions of power. Somehow, identifying the dead has become political work.

Many people have asked me what it’s like to see a dead body. I tell them that when you see a dead body, it makes you uneasy because you see yourself. You see a human being with fingers and toes, with lips and eyelashes, with moles and scars. You see someone vulnerable—no longer able to speak for herself or cover herself, no longer able to explain. You are haunted because see your future, you see the future of everyone you know. You feel you have a duty as a living person on behalf of the dead.

And we are responsible to the dead. They are always us, no matter where they are from or how they died. We are human beings, and the dead are ours. Estela is one of us. And her son should be able to visit her grave and tell his children what happened to her.

The thinking that has sustained such a deadly border for so long harms us. The thinking that explains away these deaths as the fault of those “choosing” to cross the border harms us. For that little lie is a border too. And underneath it sneaks the most dangerous threat the border has to offer—the loss of our humanity.